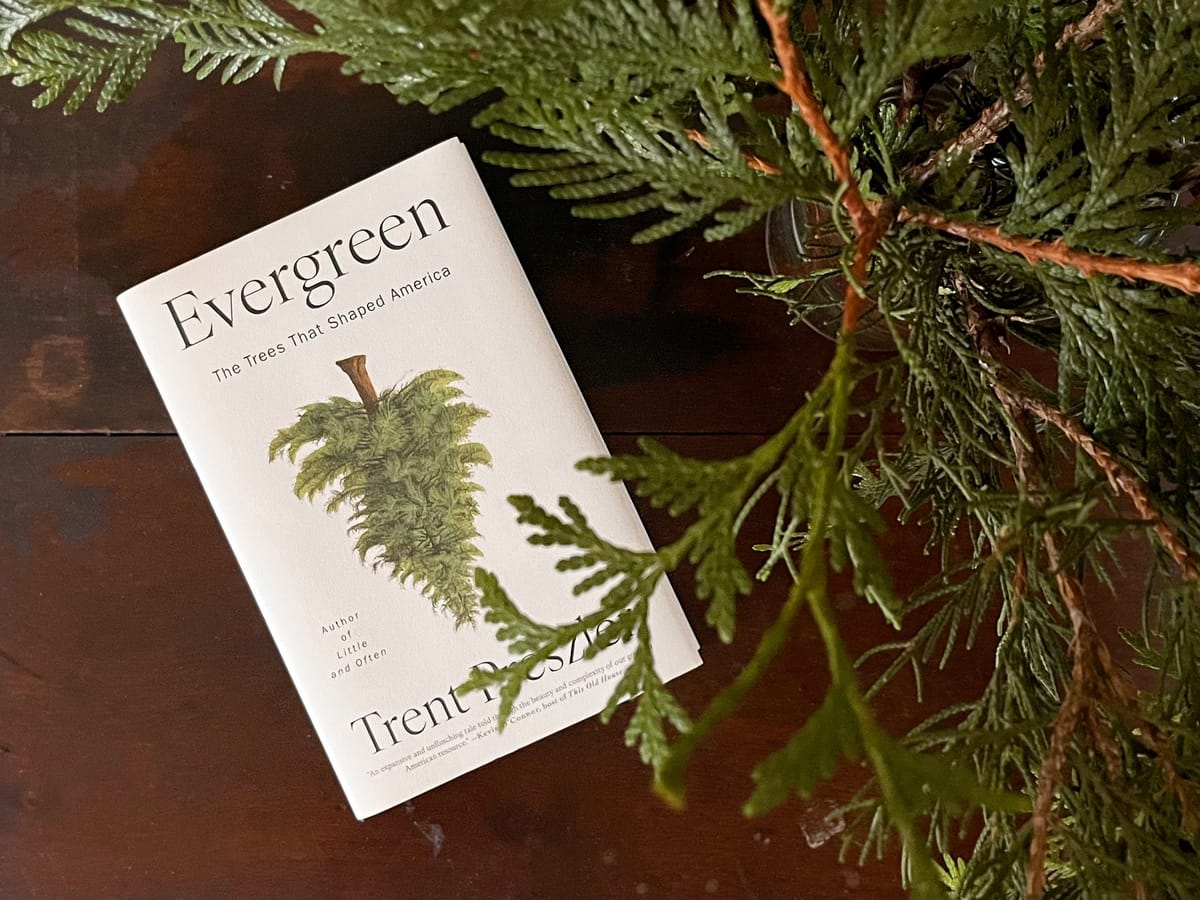

Book Shelf: “Evergreen: The Trees That Shaped America” by Trent Preszler

A brief history of repeated, short-sighted American deforestation.

Like so many movies hoping to become holiday-season staples, Trent Preszler’s slender and compelling book Evergreen: The Trees That Shaped America begins and ends with Christmas. Or with what’s come to be known as the “Christmas tree,” to be more precise. I regret that I didn’t finish it in time to tell you about it before Christmas, because with every chapter, I added another name to my list of people it would make a great gift for. While it’s a Christmas sandwich, the meat of the book is (forgive me) evergreen — the main thrust of it is the conflicted role of evergreen trees in the making of the United States of America — and it has surprisingly broad appeal.

Evergreen opens with a short cultural history of the evergreen tree in solstice season: the ancient tradition of bringing an evergreen indoors (an impulse to honor and connect with nature in the depths of winter) that was both condemned and reluctantly coopted by Christianity, eventually becoming caught in the consumerist swirl the holiday has become, with all sorts of religious and political friction along the way. Preszler takes us through everything from that to the origins and logistics of the annual Rockefeller Plaza tree, the rise of the plastic Christmas tree and corresponding demise of tree farms, and more.

Setting that particular timeline aside, Preszler then quickly traces the history of the evergreen back to pre-historic times, through the ancient Romans (“Beneath the common narrative that Rome fell due to political collapse lies a simpler truth: They ran out of evergreens”) and up to the industrial era. It’s essentially a brief history of repetitive, short-sighted deforestation in support of various capitalist or war-related causes. Preszler makes the case all along the way that evergreens (in the form of wood) are pervasive in our lives and history while that simple fact is largely invisible to us, and it’s a real mind shift to see history from the lesser- or little-known perspective of the trees.

There were the Mayflower pilgrims whose passage was subsidized by British timber barons with the expectation that they would be repaid in mast timber (among other things); the enslaved people who clear-cut pine forests in the Mississippi Delta to provide wood for fuel-hogging steamboats — land which, once cleared, became cotton plantations; waves of initiatives ranging from timber and turpentine to pencils and railroad ties (one of the most transformational events in our history), and further to plywood and MDF, with their impacts on housing and other industries. It’s a history of barons and would-be barons, one group after another who “saw nature strictly in terms of extractable wealth,” endlessly extracting.

All along the way we meet the human beings, good bad and otherwise, involved in all of this history. The Shaker woman whose invention facilitated mass logging; the Jewish World War II vet who held the original plastic-Christmas-tree patent; the many native tribes whose land and lives were irreparably damaged; and the men (many of them enslaved) who worked as lumberjacks throughout the various eras.

What could easily have been a door-stop is anything but. Preszler covers ground swiftly, and the book clocks in at just under 200 pages.

Mid-book, while reading about the culture (including the queer subculture) of the logmen who gave their lives (often literally) to the destruction of ancient trees, I was compelled to pick up where we had left off in the middle of the movie “Train Dreams” on Netflix, adapted from a Denis Johnson novella. We hit resume and were dropped into a scene where an older logger named Oren (played by the always magnetic William H. Macy) is speaking to a group of younger men sitting in the woods late one night. He says, “It’s rough work, gentlemen, not just on the body but on the soul. We just cut down trees that have been here for 500 years [or more]. It upsets a man’s soul whether they recognize it or not.” A young man replies, “I’ll have $200 in my pocket tomorrow morning. It doesn’t hurt my soul, not one damn bit.” After saying that’s because he doesn’t know the history, Oren continues, “This world is intricately stitched together, boys. Every thread we pull, we know not how it affects the design of things. We are but children on this Earth, pulling the bolts out of the ferris wheel, thinking ourselves to be gods.”

That younger man stands in for all of the barons and workmen who believed all along the way that trees would grow right back — or who cares about a thousand-year-old redwood anyway? Before returning to the Christmas tree industry, Preszler looks at modern efforts by forestry agencies, major institutions and indigenous communities — often working in tandem — to reforest some fraction of what was lost, detailing the ecological, logistical and financial challenges involved. We’ll never get back those centuries-old giants or great swaths of forests that have been destroyed, and as Preszler details, humanity has failed to learn the deforestation lesson over and over and over again. But there are so many of us now trying to learn from our predecessors’ mistakes, and anyone who reads this book will hopefully join the ranks.

It’s a great read. And I do recommend making it a double-feature with “Train Dreams.” They dovetail nicely.

BOOKS IN THIS POST:

• Evergreen: The Trees That Shaped America by Trent Preszler

• Train Dreams: A Novella by Denis Johnson, and/or the movie adaptation thereof

I participate in the affiliate program of Bookshop.org — when you buy through my links, I earn a small percentage of the sale. Thank you for your support!