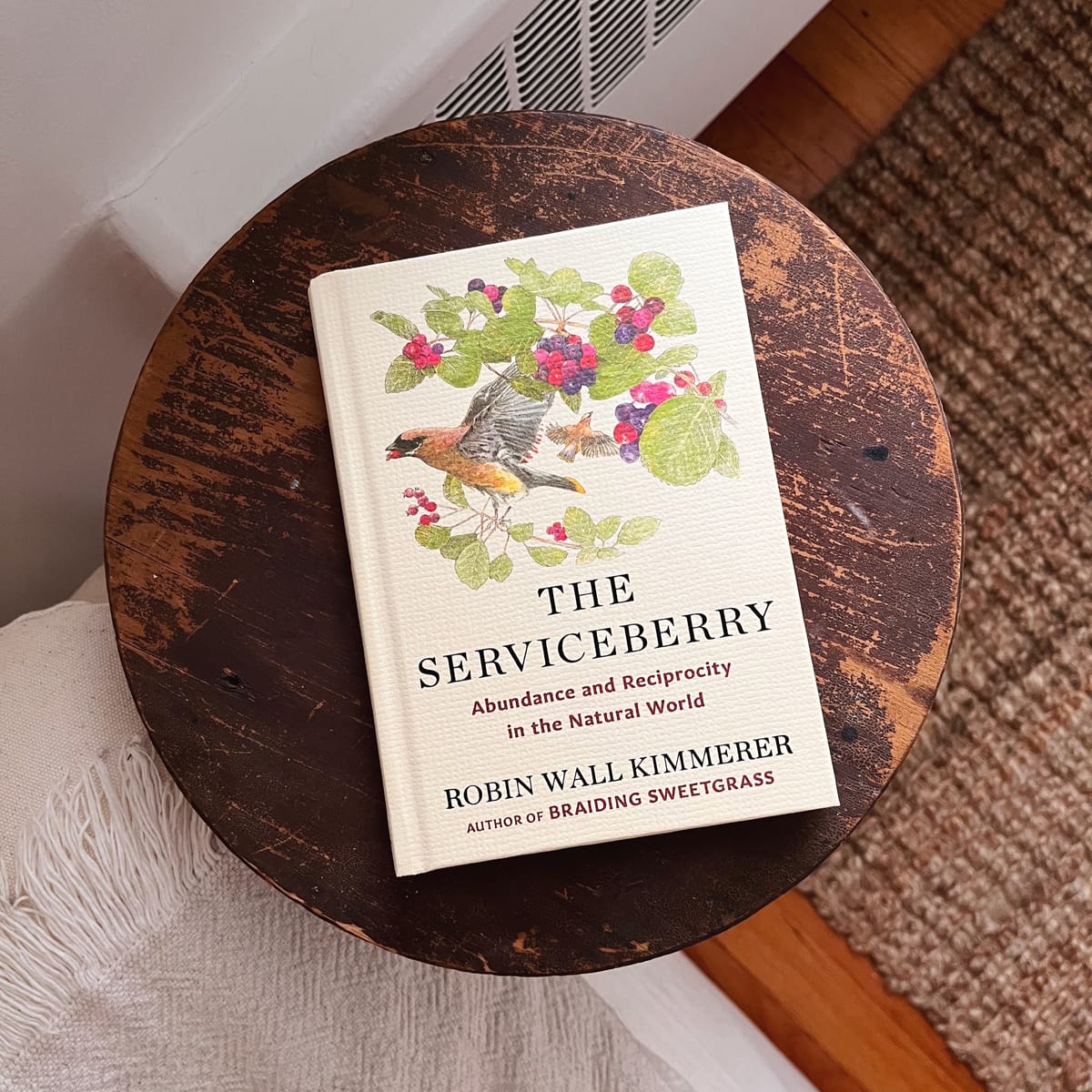

Book Shelf: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer

This small book about a culture of reciprocity and abundance is more conversation-starter than road map — but it’s a vital conversation.

On a recent Saturday, I did a little tour of my local garden centers, looking for something that might be just right for a certain corner of the garden. One of the great discoveries of gardening in this new-to-me zone is that there are season-end plant sales (!!!) that begin around mid-July, but of course things also tend to be picked over by now. On a table at one of the nurseries, I spotted a good-sized plant in great shape that seemed like just the right vibe: Shadblow, it said, specifically Amelanchier x grandiflora ‘Autumn Brilliance.’ The garden corner in question being possibly the most important of all the plant choices to be made, I went home and researched the plant, and discovered that Shadblow goes by many names — one of them being Serviceberry.

In addition to possessing pretty much all the traits I was looking for, there was a little bonus point registered in my brain for its bearing that name. People frequently ask me whether I’ve read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s ongoing bestseller Braiding Sweetgrass from 2015 (I haven’t), or her newer book, The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Apart from that well-known book title, I’d never heard the name serviceberry before. But after some consideration I went back for the plant, and a few days later I picked up the book at my local indie as well (where it always greets me just inside the door). It seemed like a two-way nudge from the universe.

Kimmerer writes: “Saskatoon, Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum, Sarvis, Serviceberry — these are among the many names for Amelanchier. Ethnobotanists know that the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural impact.” And she goes on to explain how it’s “a calendar plant, so faithful is it to seasonal weather patterns. Its bloom is a sign that the ground has thawed. In this folklore, this was the time that mountain roads became passable for circuit preachers, who arrived to conduct church services. It is also a reliable indicator to fisherfolk that the shad are running upstream — or at least it was back in the day when rivers were clear and free enough to support the spawing of shad.”

To garden is to understand reciprocity (and inter-dependency) and its role in nature, on countless levels. Take up gardening and other gardeners will immediately ask if they can share their plants and their knowledge, and you’ll soon find yourself passing along the fruits of your labor as well. You learn things like that if you want to grow food, you’ll need bees. So you ask yourself (or your neighbor) what do the local bees want that you can provide for them — as an invitation to your garden — where they’ll in turn pollinate your plants for you. When you then have too many tomatoes or zucchinis, you share them with friends and neighbors. (My favorite chipmunk is currently helping himself to my beloved ground cherries, and I don’t begrudge him.) And so on. The Serviceberry isn’t a gardening book, per se, but this is basically its central premise. Kimmerer is a botanist and a member of the Potawatomi Nation, who draws from both of those wells of knowledge in her work, and she uses the ecosystem of a serviceberry plant as the model on which she hangs her case for a gift economy — one based on abundance and reciprocity and mutual flourishing — as compared to the extractive, individualist, scarcity-based economic model we are currently ruled by.

It’s a lovely analogy, but there’s another anecdote that will stick with me (and that she also gives several call-backs), which is that of a Brazilian hunter-gatherer she read about in a book by Lewis Hyde called The Gift: “[T]he hunter had brought home a sizable kill, far too much to be eaten by his family,” and rather than employ any available preserving or storing techniques, he had invited the neighboring families to join him in a feast. When asked why he didn’t store the surplus, he was puzzled by the question and replied, “Store my meat? I store my meat in the belly of my brother.” As she says, “I feel a great debt to this unnamed teacher for these words. There beats the heart of gift economies ... .”

At the end of the book’s first chapter, she writes, “It pains me to know that an old-growth forest is ‘worth’ far more as lumber than as the lungs of the Earth. And yet I am harnessed to this economy, in ways large and small, yoked to pervasive extraction. I’m wondering how we fix that. And I’m not alone.”

That — the central question of the book — is one I ask myself every day, as you likely do too. We have to find our way back to each other on a hyperlocal level, to learn to work with each other and with the Earth (not against it or oblivious to it), as we face the concurrent collapses of our climate and our democratic social order. The Serviceberry is a very small book, a quick read, and while it’s more of a conversation-starter than a roadmap, it’s the conversation I want and need to be having with everyone around me. So I’ll press it on you, dear reader, and if you’ve already read it, I’d love to hear your thoughts. And yes, I’ll read Braiding Sweetgrass.

p.s. After I wrote this yesterday evening, I went out to tend my tomatoes, and picked the ripe Sungolds. Already having a bowlful on the kitchen counter, I walked over to the fence and hollered into my neighbors’ kitchen window that I had a handful of tomatoes for them — and they came out with an armload of peaches from their tree. Abundance and reciprocity for the win.

BOOKS IN THIS POST:

• The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World by Robin Wall Kimmerer

• Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

• The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World by Lewis Hyde

I participate in the affiliate program of Bookshop.org — when you buy through my links, I earn a small percentage of the sale. Thank you for your support!