Field Trip: Russel Wright’s living legend, Manitoga

I was not prepared for the “garden” at Dragon Rock.

Mid-Century Modern icon Russel Wright has been a design hero of mine since sometime in the early ’90s, when I first learned of his work in a formative industrial-design history class in art school, around the same time Martha Stewart was exposing him to a new generation. I’m not sure if I knew anything about his house, Dragon Rock, until seeing it lined up with many of my other favorite earthy-modern houses in Leslie Williamson’s exceptionally inspiring book Handcrafted Modern. That book has been my very favorite since it appeared in 2010, and the Dragon Rock pages are among those with the most post-it flags and eye tracks accumulated over the years. I have now lived within an hour of it for 2.5 years, and having not yet visited is why Manitoga (the name for the property on which the house sits) was on my very short list of places to see this month. So when I got an email from The Garden Conservancy about a tour that was not the standard house tour but a walk-and-talk about the landscape and Wright’s ecological approach to it, I couldn’t have signed up any faster. I knew from exterior photos that the house is in a woodland setting, the photos suggesting an almost Japanese character to the surrounding garden ... or so I thought. But nothing I’ve ever seen or read prepared me for my first glimpse of the house and its view. It literally took my breath away—

As we reached the point on the path where we could suddenly get this first view of the house from across a majestic leaf-strewn pond surrounded by cliffs, one of the women in the group said dryly, “Oh, a water feature.” Our tour guide — Manitoga’s landscape curator Emily Phillips — laughed and said what’s really funny is the boulder field across the pond is actually a waterfall, except right now not a drop of water is falling. How could the scene in front of me be even more beautiful than it was at that moment? Unimaginable.

Standing there, I realized as much as I had studied photos of the house over the years, I knew nothing about the larger property, or about Wright’s lifelong passion for shaping his landscape — which turns out to be his living legend. And I didn’t really know anything about the Wright family or their life there, in a place that was designed for enjoyment.

SHORT HISTORY OF THE WRIGHTS (gleaned from the tour and the gorgeous book Dragon Rock at Manitoga, which I brought home with me): Russel Wright and Mary (Einstein) Wright were both the artistic offspring of fairly well-heeled families, who shook off their familial expectations as lawyer (him) and socialite (her) in favor of the creative life. They met in 1927 at a legendary bohemian arts festival-community in Woodstock NY, called Maverick Festival (1916-31). He was there as a set designer and maker of various delightful things — they fell in love and were married that October. With their shared creative talents, they established themselves as Russel Wright Incorporated in NYC and began designing some of the country’s most iconic housewares, including the American Modern dinnerware line that first appeared in the ’30s and I believe remains the bestselling dishware of all time. (And has not for one single day ever looked dated or less than stunning.) As near as I can tell, construction of the house was finished in 1961, nearly a decade after Mary’s death from cancer in 1952. Russel and their daughter Annie moved there full-time in 1967.

Sometime in the ’30s, Russel and Mary started looking for a property in the Hudson Valley, north of Manhattan. They were both nature lovers, and they wanted a place similar to where they’d met. The land where Maverick took place was a former quarry (turned amphitheater) with a large meadow, and after years of searching the upstate woods for a place of their own, they found it in 1942, in Garrison NY. That pond above that took my breath away is a former quarry site, one of three on the land. In the 1800s, the property had been used for multiple extractive purposes, including granite quarried for the NYC construction industry and trees logged for firewood. When they found it, there was debris in the quarries and “second growth” throughout the woods.

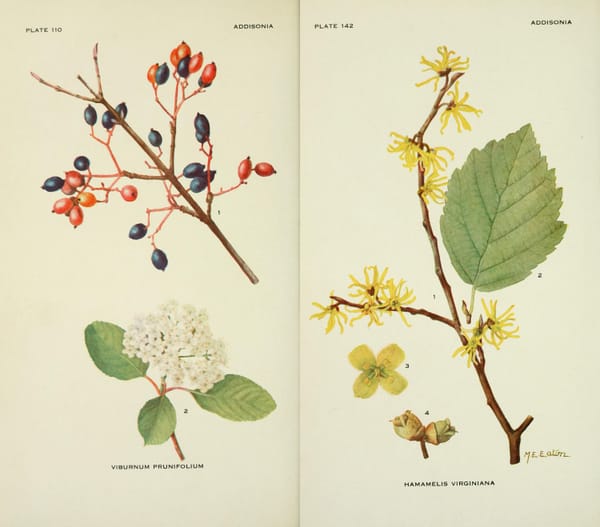

Clusters of grey birch planted by Wright in the moss on the granite opposite the house; and the curator was particularly happy to see maple-leaf viburnum making a resurgence after deer have decimated them.

One of Russel’s first gardening acts, at Mary’s request, was to make a pool to swim in. David Leavitt, the architect he would eventually collaborate with on the house, once wrote, “Being very well organized [Russel] had already settled on a site for the house, had dammed up the empty quarry to make a swimming pool, and diverted a stream which ran through the site to create a waterfall on the opposite side of the pool. He also had a detailed survey made with one-foot contours and major tree locations.” I assume that was specific to the area where the house sits, as the property was 77 acres.

That said, Wright could likely have pinpointed every tree on the grounds. While they spent many years living in an existing bungalow on the land and painstakingly laying plans for the eventual house, Russel began work on the landscape and continued honing it until his death in 1976. It’s clear he loved that piece of land passionately — his reverence still shows almost 50 years after his death. He didn’t just clear the debris from the quarry and divert a stream to fill it. He also (with help) moved boulders to enhance the waterfall. He studied every inch of the land, making surgical decisions about where to create a clearing for Mary’s desired meadow or to remove a tree (or a single limb) to open up a view.

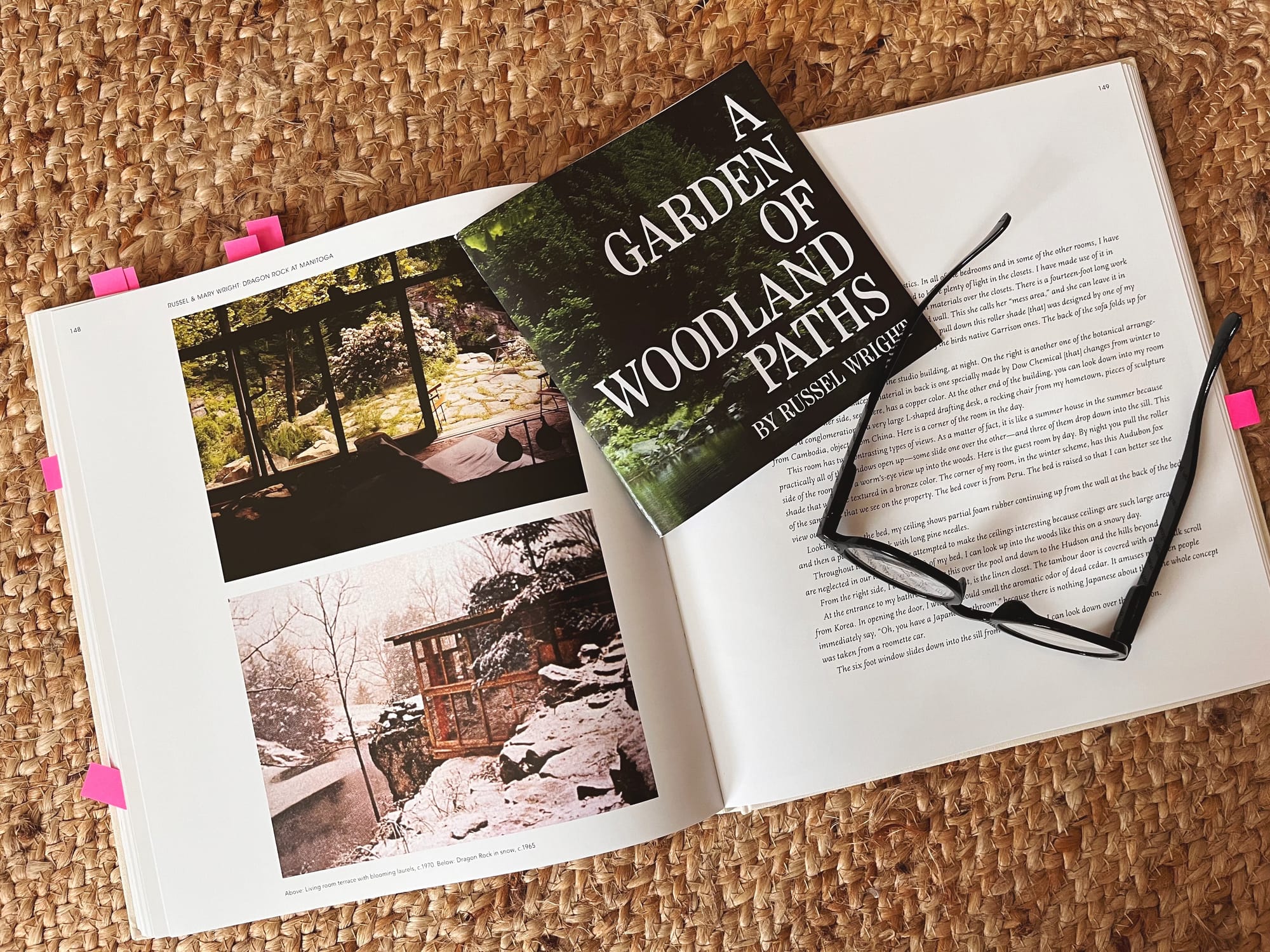

He worked with native plant species but enhanced what was there, for instance adding to the mountain laurel grove and limbing up the larger trees to emphasize the contrast between the overstory, the laurels at midstory, and the groundcovers. In a little pamphlet I also picked up while there, an essay of his published as “A Garden of Woodland Paths,” he writes about weeding around groundcovers he wanted to encourage — like the rattlesnake plantain and partridge berry that still grow among the laurels — but also hand-planting more of them. And he talks about how, why and where he created paths through the property (in addition to some that had been carved by wildlife and native forebears).

Clockwise: moss among the mountain laurels; partridge berry; waterfall bridge to the laurel grove, where Wright limbed up some of the tall trees for dramatic effect; rattlesnake plantain.

At the same time as it feels like his vision is clear, it’s impossible to know exactly what it looked like when he was there. And of course, nature doesn’t stand still. He talked over and over about the hemlocks that were the predominant feature of the forest at the time — the color of them, the way he used them to frame views and “rooms.” Few of the hemlocks he knew and loved remain today, having been decimated by pests in the intervening years. At the same time, the people who maintain this giant “wild” garden have to make choices. One of the best views is from the cliff opposite Dragon Rock, looking back toward the house. There’s a sense that this view didn’t exist in Wright’s time, due to the hemlocks, and the crew has relocated some hemlock seedlings to that edge of the cliff, hoping they’ll be able to survive. But if they do, they’ll cancel out that view. Who can know which way he would have decided on that one.

What I loved about this garden is that it doesn’t feel gardened, even though it was a collaboration between Wright and Mother Nature, and remains a managed landscape. Manitoga is the Wappinger tribe’s word for “Place of Great Spirit” and for me it honestly was a spiritual experience walking just one of the many paths.

It’s also, you might say, seductive. Standing on that opposite cliff looking at the house, I looked at our guide, Emily, and said “It’s just magical.” She responded with an anecdote she wasn’t sure she’s repeated on a tour before. Once in conversation with some people who had grown up nearby, had swam in the pond, knew the place well somehow, one of them said “There’s just something about that place that makes you want to take your clothes off.” I don’t doubt that Russel and Mary — or his late-life companion Joe — did their share of skinny dipping in the moonlit pool.

I could go on about the house itself for thousands of words, but I’ll just say this about it with regard to its landscape: They are inextricable from each other. Not only does the house disappear into the scene, it absorbs it. After much consideration, Russel chose to build it on a rock outcropping at the edge of the quarry pool. Clearly inspired by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright (no relation), stone from around the property was brought into the house for use as floors and steps and chimney. The trunk of a cedar he “found” (fallen, I assume) along the road into the property was used as a central support in the home’s common area. The walls are not only glass, they all slide or drop open so the whole place opens up to take in the pond, the waterfall, the plant life, the moon.

From the front of the house, all you really see is the pergola connecting the house and studio. The green roof has been updated with modern water management technology, and replanted.

Once inside, every room has a view, and the landscape and stone are fully incorporated into the house itself. Even the house has been gardened.

One of my favorite things in the book Dragon Rock at Manitoga is a collection of pages from a typewritten cookbook that Wright made for his housekeeper-nanny. Every recipe is followed by serving instructions, including which dishware to use, which colors, which linens, etc., all of which may vary depending on whether the meal is being served in the city or at Dragon Rock (which he refers to as simply “Garrison”) and in what season. (Don’t get me started on the seasonal changeovers to the house.) One of the serving instructions begins with “Brought in on cart.” The thing is, they weren’t fancy people. They seemed to have loved nothing more than a picnic. The house is surprisingly small and intimate, and extremely idiosyncratic. He wrote that it “must not be considered as a prototype — it is an exaggerated demonstration of how individual a house can be.” But his attention to every detail of home and land was remarkable.

He started out as a set designer at Maverick Fest and spent decades creating the set of a lifetime for himself and his family by paying attention to every branch and stone and shaft of light around him. He thought about where they would sit, swim, picnic. His paths are all named for their purposes: Morning Path (where the sun shines in through the trees), Sunset Path (self-evident), Springtime Path (peak wildflower appreciation), Winter Path (mostly evergreen) ... . He seems to have truly loved sharing it with family and friends while he was there, and then he made sure it could continue to be enjoyed by the public after his death. Although we don’t get to swim in that quarry pool.

I’m thrilled my first glimpse of it was on a beautiful peak-fall day — albeit before the winter changeover has been done inside the house. I intend to see it again in every season, and you can be sure I’ll report back. But you should absolutely go if you can.

And if I can imbue my future tiny forest with a tiny fraction of the feeling one gets at Manitoga, I’ll have accomplished my goals.

Dragon Rock / Manitoga

584 NY-9D

Garrison NY (lower Hudson Valley)

@visitmanitoga

. .

I participate in the affiliate program of Bookshop.org — when you buy through my links, I earn a small percentage of the sale. Thank you for your support!

BOOKS IN THIS POST:

• Handcrafted Modern: At Home with Mid-Century Designers by Leslie Williamson

• Dragon Rock at Manitoga by Jennifer Golub